Ever feel like it’s impossible to be a “good” woman these days?

You’re told to go after your dreams — but put family first.

Be bold — but not aggressive.

Ambitious, yet humble.

A team player — who’s also independent.

Be kind, but not a pushover.

Passionate, but not emotional.

Make people like you — but don’t be fake.

Be smart — but not so smart that other people feel stupid.

What would happen if you simply STOPPED trying to be good all the time?

What if — instead of trying to take up as little space as possible — you boldly shared your ideas, confidently displayed your accomplishments, and communicated clearly about your needs?

In today’s MarieTV, cultural expert Elise Loehnen challenges the ancient rules that hold women back, including:

- 2 surprising ways women have outperformed men for centuries

- The infuriating truth about why women tear each other down

- Why so many women don’t know what they want

- How the “morality police” hold women back from achieving their goals

- Why women put everyone else first

- The trick to making it in a “man’s world”

- How to escape the “good girl” trap

- Would you sacrifice 10 years of your life for THIS!?

Watch now and learn how to break the deep-rooted conditioning that tells women to keep their heads down, stay small, and be “good” instead of rising to greatness.

Listen to this Episode on the Marie Forleo Podcast

Subscribe to The Marie Forleo Podcast

View Transcript

Elise Loehnen:

I was like, "What's the etymology of envy? Where does it come from? Where is it in history?" Then I was like, "Oh, it was one of those sins: sloth, pride, envy, gluttony, greed." There is a playbook in our culture where we will celebrate a woman. Then she reaches a certain pinnacle where we decide she's too big for her britches. She needs to be put back in her place. This one thing that just shook me to my core was a study which was that 15% of respondents, it was majority women, would give up 10 years of their life in order to ...

Marie Forleo:

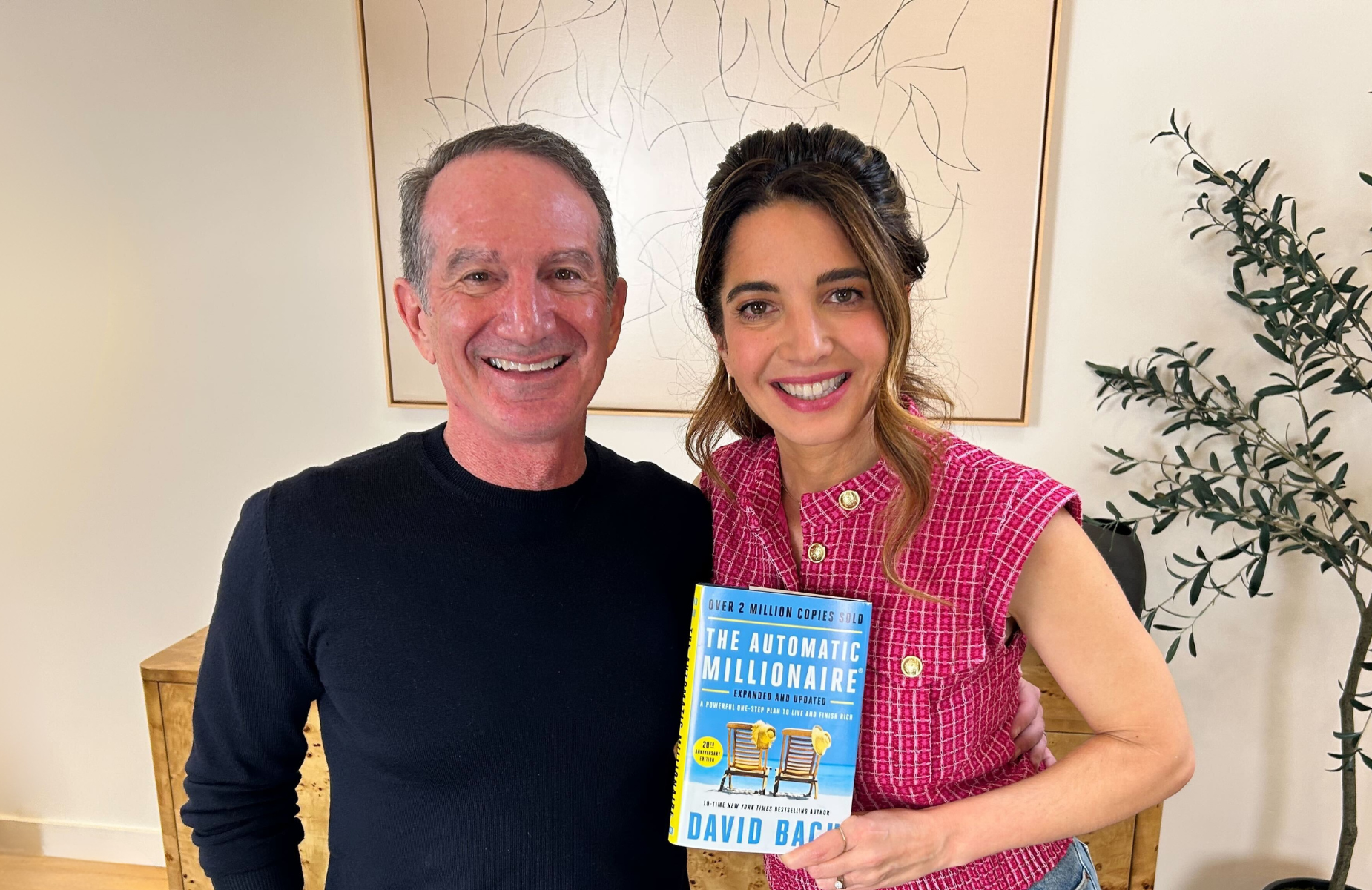

Elise Loehnen is a writer, editor, and host of the Pulling the Thread podcast where she talks with cultural luminaries on the big questions of the day. She's also co-written 12 books, including five New York Times bestsellers. Guess what? Her first book, under her own name, On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to Be Good is an instant New York Times best seller, too.

Previously, Elise was the chief content officer of Goop and led the brand's content strategy. Elise is a frequent contributor to Oprah and has written for The New York Times, Elle Decor, Stylist, and more.

First of all, okay, this book, it is so frigging good.

Elise Loehnen:

Thank you.

Marie Forleo:

Congratulations.

Elise Loehnen:

Thank you.

Marie Forleo:

All right. We were just getting ourselves our little drinks and coffees right before. Then tell me what you just said back there. Because I was like, "I did not know this. Don't say this until we're actually on camera."

Elise Loehnen:

No. Your book and you were one of the people who really actually pushed me to write a book. Because I remember distinctly and Everything is Figureoutable. Essentially, there were a few lines in there, and I am quoting from my memory, which is, this is probably four years ago, five years ago, but that it can feel like you are creating something that's already been said, but sometimes people need to hear it from you specifically. That to fixate on originality is silly in some ways.

Marie Forleo:

Yes.

Elise Loehnen:

That's a paraphrase. Then there were just nods throughout the book. Then when we met, I think we hadn't met before, and when we had our conversation and after you just turned to me and said, "But when are you writing your book?"

Marie Forleo:

Yes. I remember this. I remember this because you and I had ... first of all, I loved our connection and I loved our conversation and I think I learned how many books that you had cowritten or ghostwritten and I just felt your energy. I was like, "You are a beast." I say that in the best way, a creative beast. I was like, "Where's your book?" Or "What are you working on?" I was just so excited for you.

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. But when you need in that moment, and it's you, I can say this, but it felt like a channeled moment or push where you were just like when are you ... you saw deeply into my soul everything that I was considering but had not yet committed to.

Marie Forleo:

Yeah. I have those experiences so often and I'm always so grateful. I remember when I was just in the beginning stages of trying to write Everything is Figureoutable and I was struggling. I was so hard on the struggle bus. I was putting so much pressure on myself to be the best, which I think is something that you and I share in common. Many women, I'm sure, and men and everyone who listens to my show. I think a lot of us share a little bit of that DNA overachiever type A-ish kind of stuff.

I remember just being on the struggle bus, I was in LA, I was in Venice specifically, and I was riding my bike, and a woman stopped me and I didn't know who she was and she was so kind and she basically said, "Thank you. Your first book changed my life." It was like this little book and it's like such a sassy, silly title. It was called Make Every Man Want You or Make Yours Want You More: How to be so Irresistible You'll Barely Keep from Dating Yourself.

I wrote this when I was, the original version when I was 23. That's what I did. It's taking it back. Point is though my words on the page had made such a profound impact on her. But in that moment, I had complete amnesia and I thought I could never do it again. I was like, my stuff is shit. I also felt like such a fraud. I was like, "Look at you with this whole Everything is Figureoutable and you can't figure out how to write the book called Everything is Figureoutable.

I just so relate to those moments where I always feel like it's an angel showing up to give you that little nudge. Of course, the irony as you just mentioned, one, I think a well-written book feels effortless.

Elise Loehnen:

Or more, closer to effortless in the experience of reading it. But as you know writing a book is actually very difficult because it's a structure and it's distillation and it's really hard.

Marie Forleo:

I thought one of the things I loved about in On Our Best Behavior, first of all, you are so smart. I was like, "I always knew how smart you are and how intelligent you were." But going through this book, the mix of psychology and history and mythology and your own personal story, and I was like, "Go ladies." It's just so good.

In 2019, had you already started the book or it was more in the idea? Because I know you and I ... my book was ... how did your book come out? September of 2019.

Elise Loehnen:

Yes.

Marie Forleo:

Yeah.

Elise Loehnen:

Okay. I probably spoke to you in August.

Marie Forleo:

Yep. Exactly.

Elise Loehnen:

It was at that moment that I would even allow the idea that I would write my own book.

Marie Forleo:

Yes.

Elise Loehnen:

That's when it started. That was the door opening, that fall. I was having big moments in my career. The Netflix show was coming out, the podcast was incredibly successful and popular. Everything was great in a lot of ways. It was just a lot. It was in that moment that I just said after ghostwriting 12 books, maybe I'd done 11 by that point. But spending almost 20 years doing that for other people was the first time that I even allowed myself to consider or be open to a book.

Then the idea came to me in January of 2020 and when I was on a plane. I'd had a series of events that day. It was right before the Goop Show came out, I was on a plane. I was like, "This is what I'm going to write about," that book there.

Marie Forleo:

But how did it come ...

Elise Loehnen:

To me?

Marie Forleo:

Yeah. Do you feel like it was a download? Were you reading something? Were you listening to something? Did it show up? I often get downloads in the weirdest places like the shower, or I'm walking and it seems like it drops and I'm like, "Oh, shit, I'm going to have to do that."

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. It started because that Fall I was like, "What's my big question? What is it that I really want to understand about the world and about myself?" Because if I'm going to spend, as you know, years working on this, and then hopefully if you're lucky talking about it after it comes out and having conversations with people all over the world, it needs to be a big question.

What I really wanted to understand was, one, why are women so hard on other women? I think a lot of us have been thinking about that probably for our whole lives. But for me really started in 2016, just really starting to pay attention to culture and just understanding my own judgment of other women and starting to really evaluate that. I had probably around that time a conversation with Lori Gottlieb who wrote this book, Maybe You Should Talk to Someone. She's a psychotherapist.

She had this small moment in her book that was not a big plot point where she says, "I tell my clients to pay attention to their envy because it shows them what they want." That just dropped. I mean, again, going to this idea that you don't know how your book will impact someone. I could probably tell you nothing, almost nothing about the rest of her book, even though it's a fantastic book. But that idea just stuck in my head. Because I realized in that moment, two things.

First, I noticed that I immediately rejected the idea that I could possibly be envious of another woman. It was like, "Uh, no, never. Not me. Never. Not me." Then secondly, I couldn't identify what I wanted.

Marie Forleo:

Interesting.

Elise Loehnen:

That was a revelation. When I asked her about it, I asked her, "Is this more gendered?" She said, "I don't know the data. But I have noticed in my practice that women are very uncomfortable with things that they think are bad or unlikable qualities. They have a much harder time owning them," which makes complete sense.

That was in my head. Then in January, I went to do this media conference in Miami. It was all media executives from every single big outlet. I was being interviewed on stage. I'm pretty good with a crowd. This was a couple weeks before the Netflix show came out. Jessi Hempel was interviewing me. She was at LinkedIn. We were having a great conversation.

I could not connect with the crowd. It was so disconcerting. It was a lot of men, crossed arms. I could feel their anger and dismissiveness toward me. I'd never had an experience like that. It was so weird. Then I left to go get an Uber to go interview Glennon Doyle at a studio. This woman came up to me, was really rude, again. I was like, "This is so weird. I've never had an experience like this where you just walk into a wall of animosity."

It was just interesting. It wasn't devastating. I was just aware that I was having an experience. I was having one of those days that was full of information for me. Then I did three podcast interviews that day for three books, including Glennon for Untamed. But we had this conversation in this tiny sound booth. I was like, "Your book's going to be huge." She was like, "Like you think so?" I was like, "Oh, yes."

In that conversation, I told her about the Lori Gottlieb comment. She said, "Well, women don't know what they asked her about the wanting." She said, "Women don't know what we want because we've been told not to have any wants at all," which is very Glennon. I was thinking about that. I went to the airport. I had a very sad airport meal in a Mexican restaurant, some sad guacamole. I was just feeling so ... It was a lot.

Marie Forleo:

Yeah.

Elise Loehnen:

Then on the plane, I was emailing with my brother, who's a book editor, and I was like, "I think I need to write about envy and wanting." He said, "Uh, I don't think people want to cultivate envy in their life. I don't know." I was like, "There's something here, Ben." Then I did that. I was like, "What's the etymology of envy? Where does it come from? Where is it in history?"

Then I was like, "Oh, it was one of those sins. What were the sins?" Then I looked at the list and sloth, pride, envy, gluttony, greed, anger, and that was it. I was like, "Oh, my God. This is the checklist for everything that women consider bad to what Lori had said, and disown and disavow, and we are all contorting ourselves and living by these edicts that we might not even consciously subscribe to."

Marie Forleo:

Yeah. Let's talk about that for a second because I love how it's like, "Oh, the seven deadly sins." We know that from popular culture. We know it from the movie, and then some of us maybe have a connection to it that's more religious in nature. But I love that you're even if you are not religious, this is so embedded in even our secular culture, we don't even know it. It's like we're fish swimming in the water.

Elise Loehnen:

Yes.

Marie Forleo:

Right.

Elise Loehnen:

Oh, yeah. Because my dad is Jewish. My mom's a recovering Catholic, but I did not grow up in church. I mean, again, I had to look them up. Then to recognize the ways in which they're buried in my own. I didn't even realize when I started working on the idea. I pitched it not as a fun romp, but as an analytical, clinical history about how that exists. Then as I wrote the book and had to put myself in it and therapize myself, it's only then that I actually realized how deep it goes. But that's not how I pitched the book. I expected to hold myself apart and diagnose culture without including myself ironically.

Marie Forleo:

Interesting.

Elise Loehnen:

Isn't it funny?

Marie Forleo:

That is pretty funny. You know what? I love that in the book you talk about first and second nature. In many ways, I felt like as I was reading it, the whole book is about these guideposts pointing us back to our first nature rather than second nature. For anyone who hasn't read it yet, can you give us a little overview of first nature and second nature?

Elise Loehnen:

This is Ashley Montagu, who was a very prominent anthropologist. He wrote actually this piece, I think it was for the Saturday evening post in the '50s, called The Natural Superiority of Women, which really makes me love him. But his point was that biologically women are superior. We live longer. We obviously can create and grow life. We're more durable. We've actually been outperforming boys and men in school for a century. Stuff that I think most of us don't realize.

We might know it on some level, but I think many of us are still living in this like, "Oh, well, if we could reach the same academic excellence ..." Actually, we did that a while ago. Ashley Montagu talks about first nature and second nature. First nature being who we really are, second nature being the stories we tell about who we are.

This is really important because you see this all over the place, this idea of what it is to be a woman or a girl or what it is to be a boy or a man. We still are telling stories from our early prehistory to define who we are today, that this idea that all women are essentially nurturing, mothering, hiding in caves to take care of the children. Men are brave and valiant and hunting.

His point is, one, early people really should have been called gatherer hunters. There was far more gathering, foraging, planting than there was hunting, just much more calorically efficient. Also, we're seeing this over and over again. Again, he's not a contemporary anthropologist. He was already seeing this that our roles were much more variable and creative than this one story about what it is to be a man or a woman. We know that today, obviously.

But I write about this discovery, it was in the Amazon of 26 graves and warriors, warrior hunters, and they presumed that they were all men. Then when they took more evolved scientific ... when they looked at them again, more recently, 10 of the graves were women. We know that there were female Vikings. It just, of course, it was far more ... It might've been there might've been a majority of men who knows.

But point is we've never ever been static in our self-expression. But then when we tell stories about who we are, we continue to go back to this as, "Well, anything other than this is deviant and not who you are."

Marie Forleo:

Right. I remember I've had this conversation a couple times and I like having it repeatedly because I think it's important. Earlier in my career, and just in my life in general, I would get asked so often about having kids. I was always super clear from the moment I popped out of the womb I was like, "I don't want kids. I never wanted to get married or have kids." I remember feeling like such a deviant to use that word that you just used.

Even my mom was like, "What is wrong with you?" Now she gets it. But it's been a really long time. Just this notion that ... This is why I was so excited about your book, and we'll get to greed in a little bit, because money is one of my favorite topics.

Elise Loehnen:

I know it is.

Marie Forleo:

It's so good. I was like, "I can't wait to get to the greed section," because that's probably one of the things I love working with all humans on. But I particularly have such a large audience of women about really inspiring them to love money and to go there. Okay. First and second nature, just that inner knowing ... there's also something else I want to talk about just to note, I have always been so suspect.

I didn't grow up religious either. I went to Seton Hall University, which is a Catholic university. I loved my time there. I used to work for the church. I would help the priests get ready and I'd take care of all the different chapels. It was super fun. I consider myself super, super spiritual, but not exactly religious.

I love that you write, "The Bible is the centuries-long game of telephone edited by men according to their preferences." I have had so many instances in my life where I'm like, "Why are we following this thing that was written so long ago that we don't even know?" It wasn't until we'll get to Carissa later. But when I started really getting into Yeshua and that being is, I was like, "Yes. It's all so much." I'm sorry. You might hate me for this. But it's like, "God, so much of what we've based our culture on, and it's like there's a game of telephone."

Elise Loehnen:

It's a game of telephone. Originally, Jesus, for example, didn't write. We don't have an original copy of what became the New Testament. Originally, it was far more gospels and there's a whole process by which the Canaan came to be the Canaan, and then it was edited. There are amazing scholars in this field who can point to when the New Testament became antisemitic, for example, or misogynistic.

To go to the sins themselves, which I think many of us think, "Oh, they're in the Bible. They're certainly part of Catholicism in particular." They aren't in the Bible. Nobody sets them down in the Bible as the deadly sins. It was the 4th century, a desert monk named Evagrius Ponticus, who's also credited as one of the early fathers of the Enneagram, which is very cool.

Marie Forleo:

Wow.

Elise Loehnen:

Yes. If you follow the Enneagram, the nine points, each have a vice or a passion. The seven sins correlate, which ... What's your Enneagram number?

Marie Forleo:

The achiever. Three. Yep. I think my vice, it's vanity. I'm like, I am vain as I'm like, I own it. It's all good. But yes, not to ...

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. Yeah. When I was talking about this with my editor, when we were talking about the seven sins and the specificity for women, and I bring it back to that moment, it's not the beginning. We can talk a little bit about the formation of patriarchy if you want, and maybe who we were before that. But the morality that women in that moment became the carriers, the consigned to carry the sin is present today in a way that men are not policing themselves about their goodness.

I write in the book about how within our culture, men are programmed for power and women are programmed for goodness. We wear our goodness like a shield so fearful. Particularly now, it's almost reaching a boiling point of like, "Don't look at me. Don't cancel me. Don't come after me." Just this fear of being called bad or ambitious or greedy or slutty. All of these things that we police in ourselves and then police in each other.

Men do not seem governed by the morality police. They can do truly terrible things and they can go to prison. If we revere them, we still perceive them as powerful. We will celebrate them. We don't like weak men. But this is old. This is really old, old stuff that, again, is programmed into us from the beginning. It’s a story about what a man is supposed to be and what a woman is supposed to be. We've carried it in very unconscious ways. Then they become cultural norms that we enforce in ourselves and push on each other. It's very hard to go against the status quo.

Marie Forleo:

But awareness is the first step. I think that's why your book is so great. I want to talk. Let's get right into one of the sins. The one probably that I've had the most trouble with, sloth, I think. We'll go through each of them, and I'm happy to call myself out on everything.

Elise Loehnen:

You mean in allowing yourself to rest?

Marie Forleo:

Yes.

Elise Loehnen:

Okay. I was like, "Are you saying you’re sloth?" Okay.

Marie Forleo:

No. No. Allowing myself to rest. That's like Josh and I talk about this all the time. Because you're the most productive, always active person. But I have an ongoing narrative in my head that I feel like it's only been maybe the past three or four years, honestly, that I've been able to start to get a toehold in. Do you know what I mean? Start to really ... I'm not good at it yet, but I'm just becoming even more aware of how ... even though I know the science and the studies about how important and effective rest is and how much I enjoy ... I'm a very playful person.

I'm playing all the time. But that one, giving ourselves permission to rest and do nothing guilt-free. We have this program called Time Genius that I created mostly to help heal myself from a part of this. But we talk about that so much about how vital it is to rest.

I'll say two of the things that I have a question for you on this. I actually just realized the other night that two of my most productive spurts, where things were created really joyfully and easily, happened after long periods of rest. One was when I was struggling with Everything is Figureoutable, and actually had a two and a half week, almost three-week vacation planned to Italy that I was not about to cancel, did not care about the deadline. I was like, "I have to do this."

I remember I didn't work on the book. I didn't work on anything in Italy besides eating burrata and drinking great wine and being in the ocean. Then I came home and stuff just flowed out of me that the previous nine months, it felt like I was banging my head against a wall. Then at the end of 2020, I had a hysterectomy, because I had all these fibroids growing, I was a mess. But the recovery was basically resting for six weeks, which at least I had never done in my life.

After coming out of that, this whole program called Time Genius, it literally, it flowed out of me. I was like, "Holy, I think I need to take more time off." But it wars with the idea of, for me, being a good CEO.

Elise Loehnen:

Yes. Yes.

Marie Forleo:

I'm curious, especially too, after leaving your previous role, which had a certain cadence and a certain production where especially towards, I guess, the last bit of it, you were in front of the camera, you had so many things that you were juggling, and now though you have a whole other career and aspect of it. How is your relationship to this particular sin? How does it look different, if at all?

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. It's so deep in me. This is the first chapter I wrote. It's the first chapter in the book because it's, I think, so relatable to all women, which is this idea that there's always more to be done.

Marie Forleo:

Yep.

Elise Loehnen:

There's always doing to do. There are endless needs in the world. As women, we are certainly engineered to meet other people's needs before we consider our own or get to the whole wanting thing. We subjugate our wants to other people's needs. It's how we're acculturated. Again, do anything else, as you were just saying about choosing not to have children, it becomes a whole like, "God, Marie, that's so selfish."

Marie Forleo:

Oh. You know how many times I've heard that? Yeah. She would've been such a great mom. I'm like, "Dude, I'm a stepmom. That's really cool." But it's not selfish. It's like self-knowing.

Elise Loehnen:

Self-knowing. But this idea that you could put yourself first is so aberrant. I knew this on a mental level. That chapter originally was twice as long. I mean, I took out so many stories to make this book fighting shape, but endless stories. Every woman has endless stories. Sometimes we wear that our busyness, a little bit of a badge of honor. Again, protection against like, "Don't pick on me. Look how hard I'm working."

Again, these things are so contagious. When I think about working in a corporate culture, I had a lot of power in that situation to define my own job and determine my own output, and yet allowed to do that. I am a maniac because I recognize it in my own life. Then you create standards for output in teams that aren't necessarily balanced.

I knew that about myself, but it was also part of my perception of my own value. Look at what I'm hosting two podcast episodes a week. I am ghostwriting books. I am creating all this other content. I'm running a team. I mean like, "Look, see world. I have value. I work so hard on behalf of primarily other people, but also for myself." I had to really acknowledge that and the value that I found in that and examine that, which I'm still in the process of doing. That's the other thing. This book is a first step towards seeing how these, it's not ...

Marie Forleo:

An ongoing process.

Elise Loehnen:

It's an ongoing process.

Marie Forleo:

Like an ongoing examination.

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah.

Marie Forleo:

Have you felt like recently in terms of your own integration of, you're working and your creation in your life? I know for me, I was trying to think back to, because prior to having my business, there was a certain period of time where I had my coaching practice, but then I was in management at Crunch, and I'm teaching fitness classes and I'm doing all the things. I was like, "Oh, no. I was a maniac" when I had responsibility towards other people.

Then when it was all on my shoulders, I was like, "Ooh, I'm even worse. I can go." Are you a little easier? Is it easier for you to take rests and breaks now? Or is it ...

Elise Loehnen:

Well, I've gotten some big lessons in it. After the book went to production last summer, this sounds so extreme, but I fell off a horse and I broke my neck.

Marie Forleo:

Jesus. I didn't know that.

Elise Loehnen:

I was fine. It was miraculous. I knocked myself unconscious. I had no real symptoms outside of a lot of pain. I thought I was fine. It was at a ranch. I didn't go to the hospital. Nothing about this story makes a lot of sense. It took me a week to go and get checked, at which point I realized that my neck was broken. But because it was so stable, I just had to wear a brace for a week and do nothing.

I will say before that diagnosis, I was not doing nothing. I wasn't on a horse, but I proceeded to pack our cabin. I was there for a few more days and my kids and my husband were still riding. But I was slowly squatting so I could fold clothes and pack. I was persisting like nothing ... I hadn't just had this massive accident.

Then after I spent the night in the hospital, was put in a brace, couldn't drive. I'd been driving around LA with a broken neck. Again, this is after I wrote this book. But I remember before I went to the hospital, getting home from Los Angeles, I couldn't lift any bags. I didn't do that. But just staring at our suitcases in the living room and being like, "I need to unpack and do laundry. I need to unpack and do laundry."

Just having to sit on the couch, being in a lot of pain and just running the script and just tormenting myself because I couldn't do it. Guess what? My husband did it. I didn't ask him. I didn't say anything. He just took care of it. Then I had to, for an entire month, I couldn't drive. I couldn't cook, I couldn't clean, I couldn't do laundry. It was an incredible experience for me to just be present with myself and to hear me lambast myself, criticize myself, feel like ... Meanwhile, I found all sorts of adaptations so I could keep typing. But it was really, really an experience for me to be present in that way and incapacitated.

Marie Forleo:

Yeah.

Elise Loehnen:

Truly.

Marie Forleo:

It's wild. I often think about how torturesome it is to live in my own brain and what I say to myself and what I do to myself, even though I know better.

Elise Loehnen:

To have that script running counter to the world and my husband and my doctor and everyone saying, "Sit on the couch and watch Netflix. What is wrong with you? Stop." For me, it was almost a magnification because prior to working on this book, I had so much anger at my husband, who's a lovely guy. I'm the primary breadwinner. He also works full-time. But I'm the person who just takes care of everything. I'm very competent. There's a lot of learned helplessness in our relationship. He's very skilled at fixing all sorts of things that I'm not.

But I had also been running this resentment script of I have to do everything and, duh, duh, duh. Then in this moment after I wrote the book, and particularly my neck was broken, was like, "All right. He is not asking me to do any of this. He doesn't care about home-cooked meals and whether the floor is spotless or whether everything our kids is eating is nutritious. This is me. I'm creating all these standards. I'm the one that's enforcing these standards on myself. I'm the one who's performing this for myself and nobody else is asking me to."

Marie Forleo:

Performing is such an interesting word, too. I feel like that's so much of what you talk about and what each of these sins reveal to is our level, at least for me, I'll speak for myself, my level of performing up to my idea of being good and my idea of being perfect. I thought it was interesting. Envy, let's talk about envy for a minute. We know that that was the one where Lori Gottlieb, that one line.

This one, I've actually wrestled with it a bit in the past because there have been times when I've looked at something that someone else is either doing or has accomplished or created. I'm like, "Oh, I think I want that, too." I didn't dig deep enough because I went chasing after it going like, "Oh, well, if they can create it, I can create it too." That's my little sunny disposition and my optimism work.

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. Totally.

Marie Forleo:

Then totally found myself going, "I don't want that. It took me off track." That was my experience because again, I didn't stop and dig deep enough. I think if I were to be just a little bit more descriptive there, I didn't ask myself why.

Elise Loehnen:

What specifically? It's so much more specific.

Marie Forleo:

Yes. Let's talk about that for a minute. Have you noticed, because I love when you said at the top of our conversation where it was just like, "Oh, I think I can write this book. Wait. What do I want?" What has this revealed to you, this envy bit? Has there been anything where you've dug deeper, you're like, "Oh, I actually do want that for myself?"

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. I mean writing books and a lot of the stuff I was already doing, I just was doing it in a different context, which was keeping myself out of it.

Marie Forleo:

Hidden.

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. Using and justifying it to myself, because this is funny, I did some books a million years ago. I was in my early 20s. The first book I ever did was with Lauren Conrad. That's not funny. We did a style book together, and then we did a beauty book together. When I was working on the beauty book, I was like, "God, what is in makeup?"

This is so long ago. This is way before I went to Goop. I was like, "But she has this huge audience." There was a whole section about clean makeup. It's just funny when I was thinking about how I found ways to express myself and really go into what was interesting to me or what I wanted to say, but I found other people to say it.

Marie Forleo:

Yep.

Elise Loehnen:

I think a lot of people can probably are working for a company or working at a brand or doing stuff that's tangentially what they hope one day to do for themselves. In a lot of ways, my trajectory wasn't like a complete retooling. It was more of what would it be like if I spoke as myself and became more self-expressive and less like, "Who's the right messenger for this message? What if I just found a way to be more direct about it?"

Envy for me was ... it's interesting, and I had this conversation with Liz Moody actually on her podcast because we were digging into precisely what you were saying, where she was saying, "Well, I think I was like, I have no envy of Taylor Swift. I don't want to be famous. I don't want to be non-anonymous. It's why I love podcasts, a voice in people's ears. I don't want to perform."

She was like, "I do." In that conversation I was like ... But she was like, "I'm not a singer, but I want to be Jay Shetty. I want to be filling stadiums. I want to go out and talk to people." I'm like, "That's not the version that I want." I mean, Liz is in our world.

Marie Forleo:

Yeah. I remember when Liz Gilbert and I were having a conversation. I know that she had heard this line from Mark Manson, but it was like, "Are you willing to eat that shit sandwich?" It's a crude way of saying it. But it's like, "You can create anything you want, but are you willing to do all the work it takes to get there?"

Elise Loehnen:

Yes. That is real running it through your body and knowing who you are.

Marie Forleo:

Yes. Let's talk about that first, because I feel like running it through your body, for me, that comes down to does this feel expansive or contracted? Does my body actually feel alive and buoyant and it's moving forward in space and it has more energy versus if I'm getting myself in trouble where it's my head or my ego having an envious thing where I want that, or I should want that, my body feels dead. It feels so heavy. It's like, "I want to go take a nap."

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. Even then, it's like when you're having that envy moment, double-clicking into it to say, "But what is it?" For me, if I look at that, I'm like, "Oh, I had love to have that much." I hate the word influence. But I would love to be able to really help authors move books, for example. It's like going deeper or when you look at someone and say, "That person's killing it. But no, I don't want that level of visibility. I don't want that fame. But I am envious of their security, their financial security. How do you build a road to that?" It's finding the fractional envy points, I think ...

Marie Forleo:

I love that.

Elise Loehnen:

... can be much more helpful.

Marie Forleo:

Pride.

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah.

Marie Forleo:

This can be really complex. Where I want to get to is I'm curious to hear your thoughts about why we feel like it is so difficult to celebrate the accomplishments of women. I want to give you this. I don't know if you've ever ... have you ever talked to Regena Thomashauer, known as Mama Gena?

Elise Loehnen:

No.

Marie Forleo:

She's one of my dearest friends on the planet. I've known her forever. She is wild and smart and crazy and wonderful. She has this practice. Basically, part of her business and her career. She wrote a book called Pussy, that I encouraged her to keep with that title. It was a New York Times bestseller, and it was like, anyway, that's a different story, different day.

But one of the practices in her School of Womanly Arts is something called Bragging. It's this practice where, her and I do it together all the time, but a whole circle of our friends, we do it whenever we're talking or we're out to dinner or whatever. It's like, "Okay, who's got to brag?" We literally go around and not only do we talk about something that we're incredibly proud of, and it doesn't have to be a career accomplishment. Do you know what I mean? It could be how we showed up.

It could be something silly in our homes. Again, brags are like anything that you feel really proud of yourself for. Then we also go around and we do what I think she's called up riding, where when your friend doesn't brag, then you kind of go in and parse through who they are to have made that come to life.

Elise Loehnen:

That's amazing.

Marie Forleo:

It's almost like blossoming and fluffing on them energetically. It's amazing. Let's talk about pride for a minute. What do you think it is that society feels is so off-putting?

Elise Loehnen:

About women?

Marie Forleo:

Yeah. Celebrating ourselves?

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. I mean this idea that women need to be small and always in the house, again, in service to the world, not in the world, and focusing on servicing other people's needs is so deep in us. Then when we think about the cultural reverberations of this idea that women should really be seen and not heard, or to be behind the scenes, it's so intensely in our culture in a way that I don't think that we fully recognize.

I list these people in the book and create this arc. But there is a playbook in our culture. We're seeing this in the comebacks of Britney and all these cultural moments where we look at the ways that we've destroyed women in the past. But where we will celebrate a woman as she's emerging into the world and starting to share her gifts and then she reaches a certain pinnacle where we decide she's too big for her britches. She needs to be put back in her place. We collectively tear her down and celebrate her demise.

Whether it's Princess Diana, Billie Holiday, Anne Hathaway, Taylor Swift, I know has sort of been through this, but is still rising in part because she has an army of fans now who will protect her, which is so interesting, and I think a complete response to this particular cycle. But this is all over our culture. We don't do this to men at all.

Marie Forleo:

It's so disheartening.

Elise Loehnen:

It is so disheartening. Then what happens is there's this disconnection where we say, "Oh, well, they're famous, so it doesn't have anything to do with me." But it's a playbook. They're the most visible women, and this is what happens to them. The message for all women ...

Marie Forleo:

Don't be visible.

Elise Loehnen:

Do not be visible.

Marie Forleo:

Don't get too successful, or you're going to get knocked off.

Elise Loehnen:

Yes.

Marie Forleo:

You talked about this a lot. I have such a beautiful community. In B-School, for example. We've had over 80,000 people go through that program. I talk with so many, again, mostly women, and so much of it is actually about visibility. Because even if it's at a scale where they're like, "Okay. Nobody knows me yet. However, if I put out my ideas, my product, my service, whatever it is that is their entrepreneurial sharing, I'm going to get torn down."

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah.

Marie Forleo:

Then in other cultures, I think this is particularly true, and I think it either comes from the UK or Australia, they're connected, but tall poppy syndrome.

Elise Loehnen:

Yes, Australia.

Marie Forleo:

Yes. I hear this all the time, and of course I'm the big brash Italian-American. You know what I mean? Coming like screw that. But it's real.

Elise Loehnen:

It is real.

Marie Forleo:

Very real thing.

Elise Loehnen:

What's interesting about Australia is that Australians contend that men have this experience as well, that it's more of a cultural value for all Australians, in part, because of their separation from the UK and feeling a rejection of that type of stratified society, and that they're more collectively interested in a less hierarchical, showy way. That's interesting to me.

Because here on the other hand, where it's all sort of this fake meritocracy or talent will rise, et cetera, women are allowed to rise to a certain point.

Marie Forleo:

Then we got to knock them off?

Elise Loehnen:

Then they're done.

Marie Forleo:

Money, greed, I love money. I think that this one for me, when I was reading through, was especially resonant because so many entrepreneurs feel like if they charge what they believe they're worth for their goods or services, that somehow there's going to be less money in the world and they're somehow not spiritual, especially if they are anyone that's in the healing or helping type profession, whatever that is. It's like, "Oh, I couldn't charge that much. If I do, it means I'm an unspiritual person. It means I'm a greedy person."

Again, that's the one that for me, I just have so much fun batting down. Because I think this notion of greed, too, and you write about this, this notion of a fixed pie, it is a fallacy. There is more than enough to go around. At least that's what scarcity is. Just destructive for women. That there's not enough money. There's not enough time. There's not enough ... if you get someone else must not have, it's just like that is not only factually untrue, but it is so poisonous and it's so toxic, and yeah, anything you want to say about?

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. Well, I think this idea of greed and scarcity, for example, is a really good illustration of how these sins start crashing into each other. Even going to envy, pride, I've spoken to a lot of women who also are like, “I don't want to be seen or celebrated because I'll inspire people's envy and be put back in my place”. Then also this idea of scarcity, and that if I want something and I get it, it means someone else won't.

Marie Forleo:

Correct.

Elise Loehnen:

Meanwhile, men are not governed by these rules. They see it as a river, an endless source of growth. Whereas women perceive opportunity as more like a pond, confined, potentially stagnant, toxic. I look around, I see how men, again, prop each other up, help each other. There is an effortlessness to that. Whereas women are just inherently more constrained. Again, if I get that money, that means someone else. If she gets that money, that means I don't.

Marie Forleo:

She gets that notoriety. She gets that cover of the magazine. She gets X, Y or Z, that there's not room for all us.

Elise Loehnen:

There's not room for all of us.

Marie Forleo:

What's good news? I think that some of that is changing. Recently, I was at an event, it was actually a bunch of beauty brands. They were all coming together. I learned, and obviously I don't have a beauty product, that's not my industry, but it was just a whole group of women entrepreneurs. I thought that this was so cool. That a lot of big beauty brands right now that are run by somewhat youngish women, they're coming together and they're sharing everything.

Elise Loehnen:

I love that.

Marie Forleo:

It made me want to do cartwheels five times around the event space because they're talking about their profit margins. They're talking about their manufacturing. They're talking about what ... you know what I mean, every aspect of what they're doing to make their brand succeed. When I found that out, it almost made me want to cry. Because they were like, "Oh, yeah. We're not going to make it unless we actually share intel and do this together." I think that that's a really ... I want to support more of that.

Elise Loehnen:

Yes. There's an interesting corollary in podcasts, which we haven't broken through at this point. But you look at how men primarily in our space wellness adjacent or in wellness or wellness culture, and you watch them. Many men are dominant in that space. They all ...

Marie Forleo:

Support each other.

Elise Loehnen:

... run each other through when they have a project, they all have each other on. They'll have each other on repetitively. They've just built an extreme dominance. Again, no scarcity. It's interesting because there's not really a corollary among women.

Marie Forleo:

Yet. Yet.

Elise Loehnen:

Yet.

Marie Forleo:

Why don’t we do a dot dot dot…

Elise Loehnen:

It needs to happen because what I see, and one of the things that creates consternation for me is I feel like women tend to program a little bit more equitably. The men are not at all constrained. These guys who are so dominant and so supportive of each other, only platform men. It's sort of like a double-edged sword.

I think to balance it culturally, we really needed to get it going amongst women. Then we can platform a lot of female experts within the wellness space. There are so many academics and doctors, and yet most of those guys, when I did an audit, it's like 8% of their guests are women, not to take us totally off track, 10% to 13%.

Marie Forleo:

It's been interesting for me actually because in the specific internet marketing space, it's how I was like, "How the fuck are all these guys doing it?" Then I infiltrated it to learn. Yes. Then that's actually part of how B-School became so big, because I had, for a long time, huge female affiliates. You know what I mean? It's like …

Elise Loehnen:

You could show all of us how to do this. No. It's really interesting because I don't think that we're ... In a way, I appreciate that women don't do this or don't do it as perceptibly as men because it's so ... It's kind of a circle jerk, which is gross. I'm sorry. In a way, I am like, "Oh, I like that women don't operate by those rules." But then I look at what these guys have created and how dominant they are and the empire that they've built where they're really only talking to other men, and it's like, "Okay. Women, we should crack this. Then we can actually show how to program in a little bit more of a balanced way."

Because, and not to pick on these wellness bros, but sorry, women are out earning degrees. There are more women in medical school than men. I think in Ph.D. programs, in the medical sciences, women are out-earning, PhDs. It's like 70 to 30%.

Marie Forleo:

Wow.

Elise Loehnen:

But you don't see that represented in culture as far as ... it seems like Peter Attia and Huberman only know male academics and doctors, somehow there aren't any women to interview apparently.

Marie Forleo:

Yeah. No. I think it's interesting because I was actually talking with a friend yesterday. This was in the world, more my world of its business, and there's copywriting, and there was a particular conference. By the way, the person running the conference is a man. He's a pretty aware and striving man to have as much diversity and equity in terms of everything that he's doing.

This female friend of mine who was at the conference, she's like ... it came up to panel time and it was just all bros. We had a laugh at that because it's still very entrenched.

Elise Loehnen:

It's so entrenched.

Marie Forleo:

It's super entrenched.

Elise Loehnen:

Meanwhile, yeah, I think the world is sending a lot of ... I wouldn't even call them smoke signals. I'd say they're more obvious that people really want to hear from women and female storytellers and performers between Barbie and Taylor and Beyonce, women are propping up the economy. Yet, it's fascinating to see where people aren't catching the thread. Going back to this idea of wanting and scarcity, too, I was doing this workshop, leading a workshop maybe a month or two ago, and with a group of women who've done a lot of work together over the years.

Marie Forleo:

Yeah.

Elise Loehnen:

We asked them all to write down three things that they want, that they really, really want that they feel embarrassed to. They barely admitted it to themselves, much less said it to anyone else. It was wild because you could feel the anxiety in the room, just go to '11. I would say, I could feel scarcity along with that shame of like, "Yes. This is humiliating to think that I deserve this thing that I want and I recognize someone else might want it."

That was all to me present in this room. As we went around and women had to say it, one, it was so emotional with, again, ripping through so much shame. Two, everything that people wanted was so beautiful and reasonable. It was so wild because you would've thought from looking at this group and knowing the work that they were doing, that everyone would be somewhat in the same lane and that there would be crashing or conflicting once, or people would ... Nope, it was not.

It was like three people, maybe wanted to have a podcast. One was about palliative care. One wanted to build a regenerative farm and do ... It was so beautiful. One wanted to do stories about spirituality for children. No scarcity. Once people actually allowed themselves to say it, and instead it was just this deep recognition of, "I want that for you, too, and you should absolutely do that."

Marie Forleo:

That's so awesome. I feel like that's such a cool takeaway for anyone listening or watching right now that you could do with a group of friends, a group of people that you love and trust, that you believe in, that believe in you. What was it? What was the question? It was like ...

Elise Loehnen:

What do you really, really want?

Marie Forleo:

Yes.

Elise Loehnen:

At a level that you've never actually been able to say it or even admit it to yourself.

Marie Forleo:

I could see how that could get emotional really fast. I had to feel emotion welling up in me even when you said it.

Elise Loehnen:

What's interesting about all the sins is I think each one, each woman who's read the book has had an experience that's deepest with one of them, and several of them are so top of mind in our culture, sloth, as you mentioned, gluttony, which is baked into our culture. We have an incredibly fat-phobic society. It's part of our medical culture. It's certainly part of what's marketed to women and the way that we've been policed about our bodies.

This idea, again, when we go to first culture and second culture, that all women should be small, diminutive, little. Men should be big, strapping. This is one of those realities that we don't actually know what the reality is because you think about how we've bred ourselves into that condition, if that makes sense, through these preferences that are entirely cultural.

For example, in Catalhoyuk in Turkey, when they looked at this prehistoric site, when the world was more affiliative and partnership style, and everyone was surviving and doing life together, when anthropologists and archeologists at Stanford look at the site, men and women were eating the same calories. In many parts of the world, as patriarchy or different forms emerge, men would get favorable or more dense calories. You can see how that would inform size.

Marie Forleo:

Yep.

Elise Loehnen:

Men and women were eating the same foods. They were the same size, and they had an equal amount of kitchen soot in their lungs. They were spending the same amount of time indoors. But yet, cut to this moment in time where if you aren't policing your body, if you're not incredibly disciplined, if you're not ... you have no self-control. This myth that, "Oh, if you eat the right plate and you exercise, you'll have a conforming perfect body," which is such a myth. Every woman knows that that's a myth and yet forced on that diet.

This one thing that just shook me to my core was a study at Yale Med School, which was that 15% of respondents, it was majority women, would give up 10 years of their life in order to not be fat.

Marie Forleo:

Wow.

Elise Loehnen:

That's stunning. Stunning. 10 years. I get it. That's the sad part. I get it.

Marie Forleo:

Yeah. Well, it's how we've been trained.

Elise Loehnen:

It's how we've been trained.

Marie Forleo:

It's like every image that almost, not all, but many women have seen since the moment we could see images.

Elise Loehnen:

Yeah. To be good and to be bad is there's no more clear language, an idea of that as when it comes to food and our bodies. I was bad last night. I need to be good today.

Marie Forleo:

Yeah.

Elise Loehnen:

The way that we moralize, it's wild.

Marie Forleo:

The amount of times that I've said that to myself. Oh, I was just so bad, so bad. I had that piece of cake.

Elise Loehnen:

Penance. Yep. Now we have to do penance. Yep.

Marie Forleo:

Yeah. Elise, you are amazing. Thank you for taking the time really to come and to talk about this. Thank you for stepping out and continuing to share who you are and all of the brilliance in your mind and your heart with us.

Elise Loehnen:

Thank you.

Marie Forleo:

I'm very excited for all of the things that you'll continue to create and for us to have many, many more conversations.

Elise Loehnen:

Well, and thank you for blazing trails and pushing up against all of these ideas, particularly around scarcity, because I think when we see the truth, the world will change enough for all of us.

Marie Forleo:

Amen.

DIVE DEEPER: Want more help escaping the “good girl” trap? Grab my ultimate guide for saying “NO” — including 19 word-for-word scripts for almost any situation.

GRAB ELISE’S NEW BOOK: On Our Best Behavior: The Seven Deadly Sins and the Price Women Pay to Be Good

Now it’s your turn. Let’s look closer at the “7 Deadly Sins of Being a Woman.”

For example, mine is Sloth. I tend to push myself way too hard — always striving to do more and give more — to avoid looking lazy. Even though, deep down, I know I’m doing more than enough. What about you?

Which of these do you catch yourself feeling guilty about the most?

- Sloth

- Pride

- Gluttony

- Anger

- Greed

- Lust

- Envy

Write 1–2 sentences about why it makes you feel guilty. Now ask yourself: is this feeling real? Or does it feel like something you’ve been programmed to believe?

What’s something you could do (or stop doing) to write a new truth for yourself?

Share your thoughts in the comments below, and let’s help each other escape the “good girl” trap together.

XO

View Comments

View Comments